No, Donald Trump, America Didn’t Win the War Alone

How Hollywood, hubris, and historical amnesia erased Canada’s sacrifice in Normandy

Capt. Hamill: What've you heard? How's it all falling together?

Capt. Miller: Well, we've got the beachhead secure, problem is Monty's taking his time moving on Caen, we can't move out 'til he's ready.

Capt. Hamill: That guy's over-rated.

Capt. Miller: No argument here.

We’re now two days past the 81st anniversary of the invasion of Normandy by the Western allies - D-Day. And every anniversary, I think of that movie and that scene with Tom Hanks and Ted Danson. It is, of course, Saving Private Ryan and the scene is a great example of how American distortions of history creep into everyday conversation.

Don’t get me wrong. I enjoy the movie and I do understand that it’s written for an American audience from an American perspective. But the impact in Canada, where the public often conflates U.S. history for our own, is considerable. Most Canadians have very little exposure to Canadian historical perspectives after they finish high school. Canada is awash in US media and, especially with military matters, Canadians confuse American history with our own. So I’ve decided this time to talk about D-Day and how our history gets warped by (largely) American mythology.

First, let’s briefly discuss the common narrative perpetrated by US media. That is: the United States, supported by myriad other minor allies, planned and conducted the invasion of France. On D-Day itself, they undertook the bulk of fighting, especially on Omaha beach, while the British (Canada doesn’t rate a mention) were bogged down on their beachheads. British caution and reluctance to take casualties resulted in their failure to take the town of Caen on the first day and they dragged their feet for weeks afterwards, causing delays and more American casualties. Finally, the narrative states, American skill and aggressiveness enabled a break-out from the bridgehead under the leadership of General George Patton, about whom another mythological movie has been made. It was an American war after that.

Yeah, about that.

Virtually everything in this common narrative is wrong. Yet, if you asked Canadians with a passing knowledge of the event, this is likely what they’d tell you.

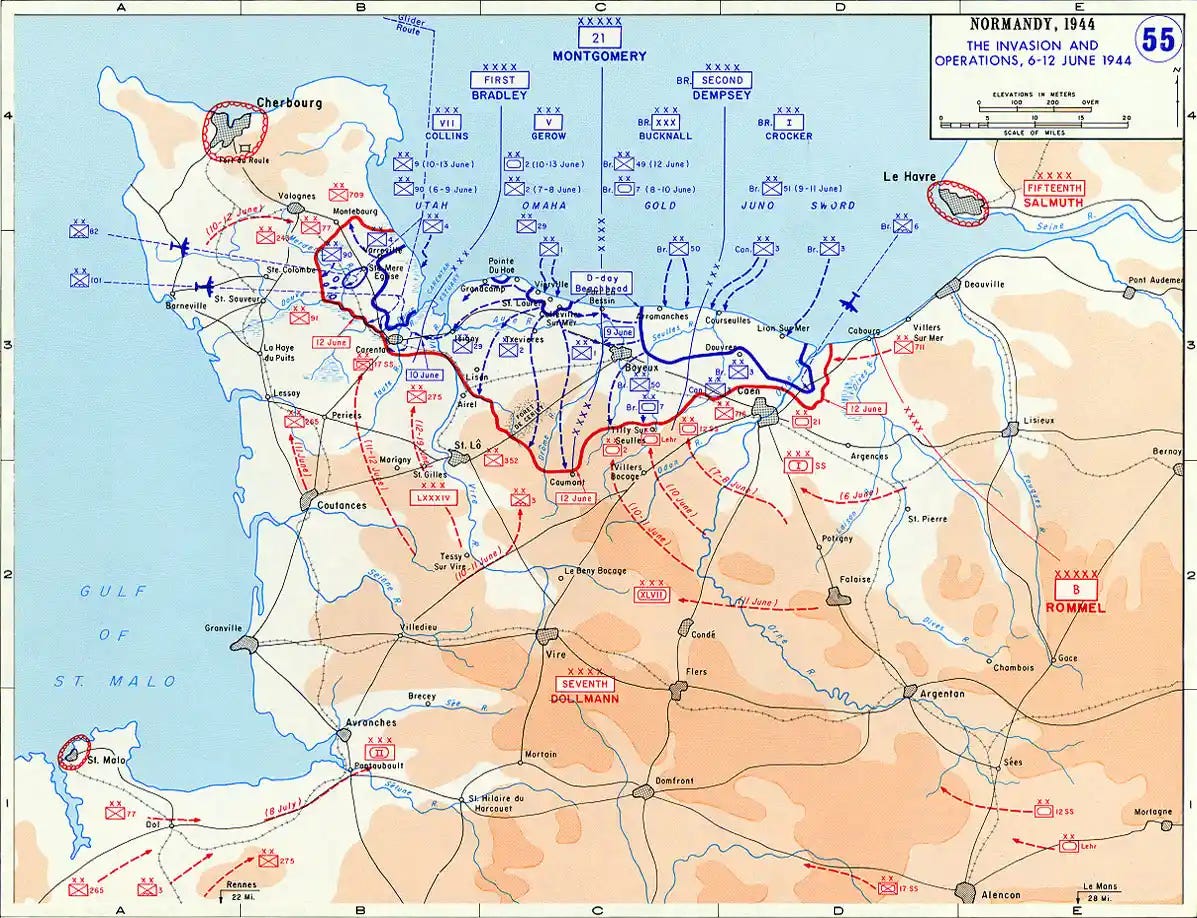

To begin, let’s take a look at the map:

This is a military map of Normandy and uses military symbology to represent units and movements (the map can be enlarged here). The Allies are in blue while the Germans are in red. You can see the Allied forces at the top of the map, with the 21st Army Group at the very top under Field Marshal Montgomery, who was responsible for planning ground operations. The forces actually assaulting the beaches are depicted under him, along with the five beaches, two American, two British, and one Canadian, running west to east. The British and Canadian beaches are on the eastern side of the assault, in front of the town of Caen.

The thick blue line represents the limit of the Allied advance at the end of the day on 6 June. The thick red line depicts the limit of the advance on 12 June.

Now we need to get technical for a second. Note the symbols on the map.

This symbol -

Represents armour or tank units (the oval represents a tank’s track).

This symbol -

Represents infantry - without armour (the cross represents a soldier’s cross belt).

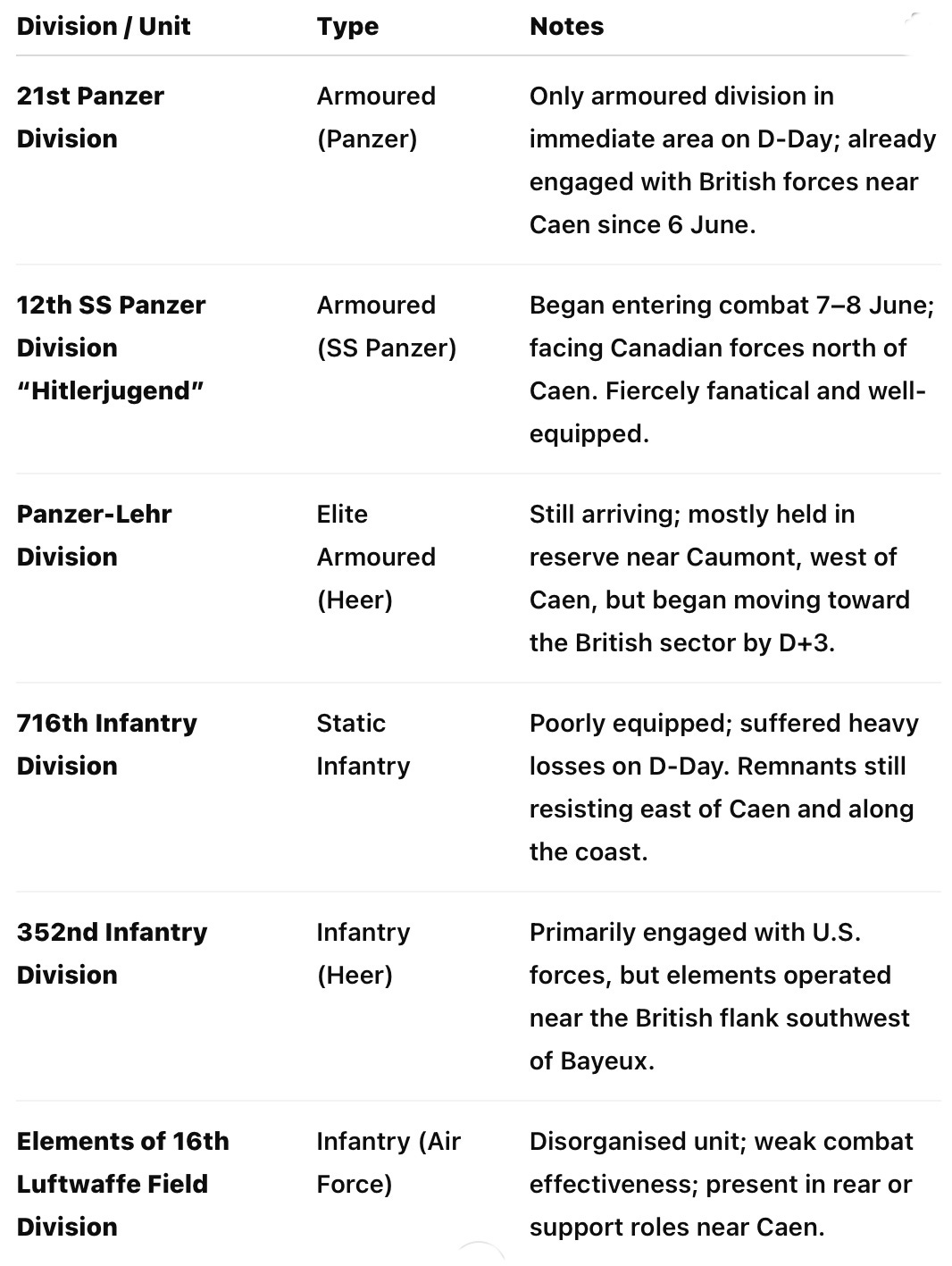

Now let’s go back to the map. German forces, represented in red, have concentrated the *vast majority* of their combat power, including all of their armour, against the British and Canadians. This included:

So, almost immediately the British and Canadians faced the vast majority of German heavy units and would continue to do so for several weeks, including through brutal fighting to liberate Caen and push south. This cost both formations dear as untried Anglo-Canadian troops equipped with the somewhat lacklustre Sherman tank met fanatical, combat experienced German units equipped with Panther and Tiger tanks. British and Canadian losses in armour climbed dramatically, as did the casualty count.

This isn’t to say that the Americans, facing much lighter units, were having an easy time. The hedgerows and deep-sunk roads of western Normandy and Brittany were extremely difficult terrain to navigate and easy for the Germans to defend, even with light forces. Moreover, the US was tasked with clearing Brittany and seizing the port at Cherbourg, the latter heavily defended by a specialized German garrison. Finally, their buildup of forces had to continue, all performed while shipping all personnel and equipment across the beaches at Normandy.

“Fixing” Operations

If all this looks a little odd, it’s because it is. It’s because this is what military planners call a “fixing” operation whereby one element of a force attracts the bulk of the enemy and draws it to itself, enabling another element to undertake its operations relatively unhindered. In Normandy, Montgomery, the overall planner of ground operations had this, or something like it, in mind from the very outset. To be sure, it was optimal if Caen and the terrain behind it could have been captured on the first day, but the presence of the German 21st Panzer Division and the early arrival of the Panzer Lehr Division likely made that impossible (as an aside, Lehr means “school”, an indication that it was fairly expert).

So the mission of the British and Canadians became to draw in the German armour, to “fix” them in place, and to prevent it from engaging the Americans to the west. This enabled the Americans to clear their bridgehead, capture the port at Cherbourg, and to conduct a build-up for what was to come. The Anglo-Canadian allies conducted nearly a half dozen named operations aimed at drawing the Germans to them and to batter their way through the lines past Caen. It was indeed slow, but it cost both the UK and Canada thousands of casualties and the loss of hundreds of tanks and other armoured vehicles.

The British and Canadian offensives were deliberately costly operations intended to pin down German panzer divisions. They were effectively sacrificial attacks that ensured the success of the American breakout by preventing German mobile reserves from shifting west. (Antony Beevor, D-Day: The Battle for Normandy, 2009)

And so it continued through June and the first half of July 1944. No one had it easy, but I would argue that the British and Canadians had it the worst - all for good reason. As late as mid-July, when a movement west to engage the Americans by the 21st Panzer was detected, the Anglo-Canadians mounted another spoiling operation, as can be seen from this quote from a 2 Canadian Corps operations order (Operation ATLANTIC):

To draw enemy formations away from First US Army front by attacking southwards with 1, 8, 12, 30 and 2 Canadian Corps. (2nd Canadian Corps' Operation Instruction No. 2, dated 16 July)

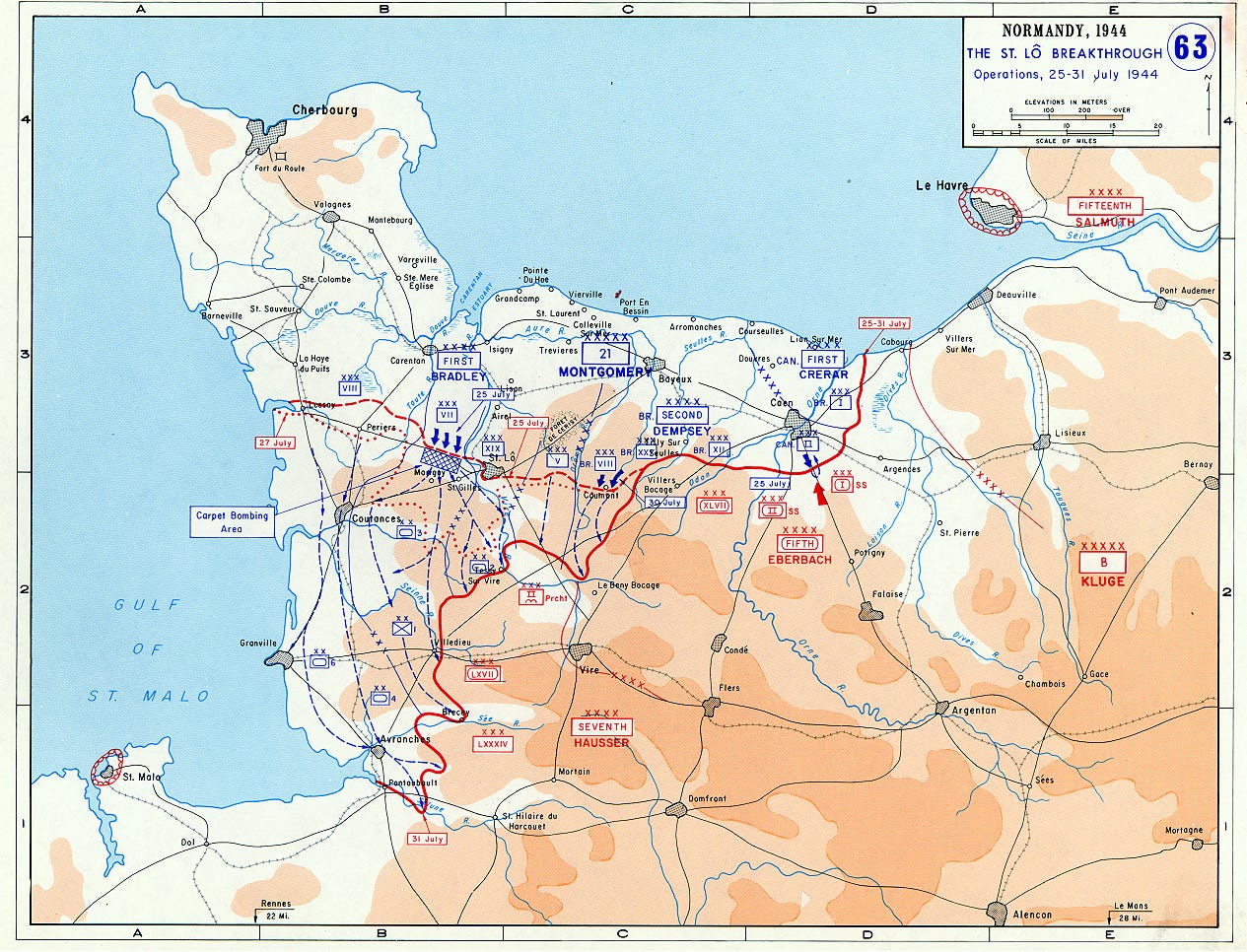

Operation COBRA

All of this, of course, had a purpose: to enable an American build-up and a subsequent massive break-out operation called Operation COBRA. The British launched Operation GOODWOOD and the Canadians began Operation ATLANTIC all designed to distract the Germans from the the US offensive, which kicked off on 25 July. While the Anglo-Canadians held the German armour, the American blasted their way through the German’s left flank and began the sweeping advances that allowed them to push right up to the Rhine within a few months. American units poured into France and their number quickly surpassed all the other Allies combined. The US came to dominate the Allied operations in the West.

Epilogue - Falaise

There is, of course, an epilogue. As the US First Army swept through Western Normandy and swung around towards Germany, it became obvious that the bulk of German forces were likely to be trapped in a “pocket” in the neighbourhood of a small town called Falaise. By mid-August, the Third US Army had reached Argentan, just south of Falaise, where they were ordered to halt by the US commander, General Bradley, who refused to allow General Patton to close the pocket from the south. This task fell upon the British and Canadians, joined by the gallant Poles, who still faced the vast majority of German heavy units, including five panzer divisions. Faced with this opposition, the Canadians and the Polish struggled to close the pocket and significant German forces escaped. Once again, some Americans have accused the Canadians and Poles of being “slow”, and of lacking the offensive spirit of Patton and his units. Ironically, it was the Americans who were risk-averse in this case.

So What?

So, BC6, why the half-assed history lesson? Because American reliance on mythology such as the view perpetuated about D-Day affects US views of its Allies to this day. To a significant segment of Americans, we should be “grateful” that the US won the war for us. But the fact is that the US couldn’t have “won” the war without us, particularly in the months before personnel and materiel superiority caused them to dominate operations in the West. US mythology affects their relations to this day and creates a mindset where they are owed by the rest of the world and are - to some measure - superior to everyone else. This kind of myth-making isn’t just harmless storytelling. It feeds into a broader American worldview that consistently overstates its role in global affairs — a view that’s alive and well today. Need an example? Here’s Trump repeating what he’s often said:

As much as I enjoyed the reading part, I could have done without Trump's take on this 🤥. He's once again wrong, (as he usually is) and obnoxious to boot. I visited Caen, Dieppe, Juno Beach as a teenager while living in Germany (my father was in the infantry, R22R). It has always rubbed me entirely the wrong way to see how Americans act as if "they alone" won the war/s. It is really sad that our younger generations only know the "Hollywood" version. Thanks for the post.

Thank you most sincerely for this excellent analysis. I’m going to be at Juno Beach in August with my granddaughter and will share this with her. 🇨🇦